Little Black Angels

(Angelitos negros)

Not many people know that Andrés Eloy Blanco, one of the most prominent Venezuelan writers of all time, was the author of the poem Angelitos negros, Little Black Angels. The poem became the lyrics of the popular song of the same name, which traversed the borders of Venezuela to re-emerge as an anthem against racism in Latin America. It was in this form that I first heard Angelitos negros, and my favourite version is the one by the Venezuelan singer Soledad Bravo. Please click here to listen to this version.

Andrés Eloy Blanco

In my previous article La Copla, I discussed the phenomenon that occurs when a piece of art is somehow appropriated by its people. Similarly, Angelitos negros [1], transcended its creator’s vision to become part of Latin American folklore.

It is said, that Andrés Eloy Blanco [2] may have been inspired by a painting located in the Macarena Basilica, in Seville. The image of the Virgen de Coromoto. Comoroto’s Virgin, Venezuela’s patron, is surrounded by angels, however there are no black angels depicted within this heavenly host.

The poem Angelitos negros starts off by describing the profound sadness of Juana, a woman of African origin, whose little son has died. The second verse is very significant as it describes the mother and her son, “consuming themselves”, suggesting that both are malnourished:

Como ella se consumía,

lo medía con su cuerpo.

Se le iba poniendo flaco

como ella se iba poniendo.

— & —

As she consumed herself,

She measured him against her body.

He was becoming as thin

As she was. [Free translation]

Juana, in the midst of the devastating pain at the loss of her son, hopes that he will be with God. A little angel in the sky, she says. The narrator of the poem counters Juana’s fervent wish; Disabuse my friend, there are no black angels.

It is, lets say, more often than not that white angels surround the Virgin in any painting.

The poet directly addresses the artists of his homeland, these painters of saints and Virgins, reproaching them that they do not paint black angels; and in failing to do so they had denied their own kind. The poem eloquently asks for equality:

No hay pintor que pintara

angelitos de mi pueblo.

Yo quiero angelitos blancos

con angelitos morenos.

There is no painter to paint

angels of my people.

I want white angels

with dark angels. [Free translation]

Andrés Eloy Blanco (1896 – 1955) wrote this poem at a time when issues of racial discrimination were not on the top of the Venezuelan political agenda. His honest views of the world gave voice against the racial discrimination perpetuated in religious art. This was, in many ways, a milestone even in the decades that followed. He remarks in the poem:

no hay una iglesia de pueblo,

donde hayan dejado entrar

al cuadro angelitos negros.

— & —

there isn’t a village church,

where they have allowed

black angels to be painted. [Free translation]

Andres Eloy Blanco is considered to be one of the most talented Latin American poets whilst simultaneously being an adept lawyer and politician. His polemical discourse portrays his concerns about his country and world affairs, which ultimately led him into exile.

Francisco Camacho, Venezuelan university professor, stated that Andres Eloy Blanco lent his poetic talent to those who had no voice and that they could see themselves reflected in his verses [3]. Some political and literary commentators compare this song with the speech of Martin Luther King I have a dream. Andrés Eloy Blanco always condemned intellectual opportunism and had an uncompromising view of the world where ethics should not be negotiable.

Cover of The best of Toña “La Negra”.

The Mexican singer Toña “La Negra” (1912 -1982) was the first to interpret the song Angelitos negros, followed by the Mexican actor and singer Pedro Infante (1917-1957). In order to listen to the version of Toña “La Negra” please click here and for the version of Pedro Infante in the 1946 film Angelitos negros, please click here.

The version sung by Antonio Machín (1903-1977), a Cuban singer, is considered by many to be the best version and it has retained its popularity to this day. However, many other very interesting versions have been recorded over the years keeping this song alive. Please click here for the version of Antonio Machín with the lyrics in Spanish.

Spanish, like the English language, has had a global impact due to its history of proactive colonisation. The power of a word is such that a language mirrors and transmits cultural and moral values of a society, reinforcing them. Angelitos negros is a good example where the model of exclusion is applied in religious art.

Pedro Infante in the 1948 film Angelitos negros.

In 1492, the Spanish Empire began their process of expansion, known as “colonization”. In Latin America the Spanish Empire established a model of exclusion of African and indigenous peoples based upon a racial hierarchy, which still prevails to this day. The use of words such as mulatto (mulato in Spanish), mestizo (mestizo in Spanish) and black (negro) have been part of a large jargon of words which stigmatize, to economically exclude these social ethnic groups.

This “concept of races” and racial stratification perpetuated economical exclusion and has brought devastating consequences to the indigenous and black communities in Latin America to this day.

Angelitos negros gives us another great opportunity to explore different variations of a song to discover which of the many versions is our favourite one. I would like to invite you to surf on YouTube and find your favourite version. Have you found one that you would like to share with us? Please add it below with your comments.

January 2016

Footnotes

[1] For an electronic copy of the poem Angelitos negros in Spanish, please click here.

[2] For further information on the life and works of Andrés Eloy Blanco, please click here to a pdf in Spanish of his biography: Andrés Eloy Blanco y la posteridad, Andrés Eloy Blanco and Posterity, by Oscar Sambrano Urdaneta, Universidad Nacional Abierta.

[3] Free translation from: Prestó su talento el poeta para que los que no tenían voz se vieran reflejados en sus versos. Fragment from Andrés Eloy Blanco: periodismo, modernidad, y política en la Venezuela de la primera mitad del siglo XX, page 22, Profesor Francisco Camacho, Instituto Universitario Experimental de Tecnología Andrés Eloy Blanco. Barquisimeto, Universitary Experimental Institute of Technology Andrés Eloy Blanco, Venezuela.

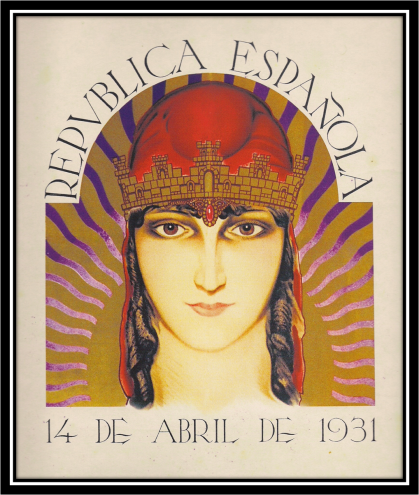

La Copla

On the cusp of 20th century, amidst the cafés cantantes and cafés de marineros, bars with live music and those frequented by sailors, the more cosmopolitan ‘ambientes‘ [1] of Spain gathered to indulge in the bohemian lifestyle. One can only imagine the subversive appeal of such illicit places, with drinking and both flamenco and pasodoble performances, attracting thrill-seeking members of a conservative society to a risqué underworld. This vibrant scene gave birth to the Copla.

As with all partisan movements a counter-narrative develops. The lyrics of Ojos Verdes and Las cosas del querer (as discussed in my previous two articles), and of the majority of coplas, are made up of language, both direct and colloquial. They are filled with innuendo and double meaning to avoid censorship of forbidden or marginal themes: social division, gypsies, imprisonment, prostitution, good and bad luck, forbidden or hidden love and homosexuality.

The people sang because music would have kept spirits high during the tragic 1930’s. The pain and suffering was well portrayed in some of these lyrics, such as: “Gypsy woman wandering across the world, singing and dancing, singing I seek relief of my grief” [2].

Suspiro de España, Sigh of Spain, may have been the first copla ever written [3]. This was performed in the film of the same name by Spanish singer and actress Estrellita Castro (1908-1983). The lyrics reflected the nostalgia of those forced to go into exile during the Spanish Civil War and of their love for their homeland. To listen to the version by Estrellita Castro please click here .The song starts at 2.05 minutes.

The copla La Diputada, The Congresswoman, first sung by Amalia Molina in 1932, is a clear example of strong feminist lyrics. To listen to the song: please click here [4]. Please see below a fragment of the lyrics in Spanish and English:

Llegó la hora del feminismo,

y como siempre fui avispada,

y en todas partes me llevo algo,

me llevé el acta de diputada.

En el congreso con Luis de Tapía,

estoy actuando de adalid,

¡Viva el divorcio! ¡Vivan mis manos!

Qué aún no han cosido, ¡ni un calcetín!

— —

It has arrived the time for feminism,

and as always I was shrewd,

and as everywhere I achieve something

I took the role of deputy.

At the congress with Luis Tapia,

I am acting as champion,

Long live the divorce! Long live my hands!

They have not yet sewn, not even a sock! [5]

The radio was central to popular post-war entertainment, also post-war the Copla was the only genre that pushed the boundaries of what was permissible to sing, touching on the thorniest issues as no other genre did at that time.

It is noteworthy that whilst coplas appeared to have sprung from the bohemians and Republicans of Spanish society, the Franco propaganda regime would appropriate those symbols, which Spanish people could identify as Republican, and turned them into the “official” Spanish popular culture.

Concha Piquer (1906-1990) one of the most renowned and talented interpreters of coplas is associated with the Franco regime. Some people nowadays unfairly only see the coplas as the official music of the Franco regime in Spain and therefore as something to reject.

Three of the most representative authors of coplas are Rafael de León, Manuel López Quiroga and Antonio Quintero, together known as the Trio Quintero. Rafael de León, considered to be a poet of the 1927 generation, wrote approximately 5000 coplas with Antonio Quintero and Manuel López Quiroga and 8000 in total.

Many others are worthy of mention, amongst them Antonio Machado, Federico García Lorca, Violeta Parra and Jaime Dávalos, to name a few of the Spanish and Latin American artists who have written unforgettable coplas.

Coplas are the voice of the Spanish people at a significant time in their history, regardless of whether or not coplas were Republican born or fostered by the Franco regime I am of the opinion that they belong to the people and , as Manuel Machado (1874-1947) says:

Until people sing the coplas, there are no coplas, and when the people sing them, then nobody knows the author. Such is the glory, Guillen, of those who write songs, to hear people say that no one has written them. You hope that your coplas end with the people, despite that they will no longer be yours and will belong to everybody else. That is when you melt your heart in the popular soul. What is lost of recognition is gained in eternity [6].

September 2015

This is a follow up to two previous articles: The Things of Love and Green Eyes, published in August 2015.

— —

Footnotes

[1] Ambiente: ambience, set of characteristics of a social group.

[2] Free translation from: Gitana, gitana, gitanilla errante cruzó el mundo entero, cantando y bailando buscó en las canciones alivio a mi duelo.

[3] Suspiro de España was written by by Antonio Álvarez Alonso and composed by Juan Álvarez

Alonso.

[4] La Diputada was written by De Carrere and Font de Anta.

[5] Fragment from the copla La Diputada, free translation.

[6] Free translation from the poem:

La copla

Hasta que el pueblo las canta,

las coplas, coplas no son,

y cuando las canta el pueblo,

ya nadie sabe el autor.

Tal es la gloria, Guillén,

de los que escriben cantares:

oír decir a la gente

que no los ha escrito nadie.

Procura tú que tus coplas

vayan al pueblo a parar,

aunque dejen de ser tuyas

para ser de los demás.

Que, al fundir el corazón

en el alma popular,

lo que se pierde de nombre

se gana de eternidad.

To listen to La copla of Manuel Machado recited by Vicent Camps, please click here. Only available in Spanish without subtitles.

Green Eyes

(Ojos verdes)

We knew when dad was happy in the mornings. He used to sing the songs he learned from grandma Chiquita (Petit), as we used to call her. Dad used to sing Ojos verdes, Green Eyes, one of the greatest coplas of all times. He said that Concha Piquer made this song known in the film Filigrana, Filigree, in 1949. As with any other great song, the genesis of Ojos verdes has its own legend and my dad’s account may not be have been the whole story.

I still remember the chorus that my father used to sing:

Ojos verdes, verdes como la albahaca.

Verdes como el trigo verde

y el verde, verde limón.

Ojos verdes, verdes, con brillo de faca,

que están clava(d)ítos en mi corazón.

Pa(ra) mí ya no hay soles, luceros ni luna,

no hay más que unos ojos que mi ví(d)a son.

Ojos verdes, verdes como la albahaca.

Verdes como el trigo verde

y el verde, verde limón.

— —

Green eyes, green as basil.

Green like the green wheat

and the green, green lime.

Green eyes, green, with the brightness of a dagger,

They are nailed in my heart.

For me there are no suns, constellations or moons,

There is nothing else than those green eyes that are my life

Green eyes, green as basil.

Green like the green wheat

and the green, green lime. [1]

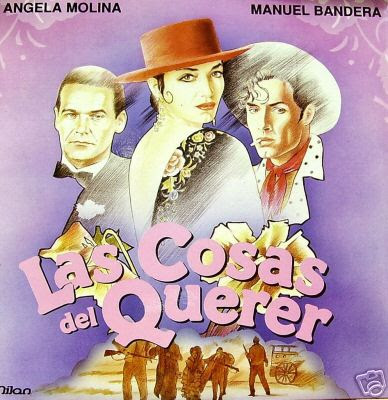

In 1989, I heard a new version of Ojos verdes by Manuel Banderas, in the film Las cosas del querer, The Things of Love. The screening awoke my curiosity as to who could have inspired such a masterpiece of Spanish music. To see a clip of Manuel Bandera’s version please click here.

In 1990, fifty years after his exile from Spain, Miguel de Molina (1908 – 1993), one of the most renowned Spanish copla singers revealed, during an interview to the Spanish channel Canal Sur, significant details of the very first moments when the lyrics of Ojos Verdes were written [2].

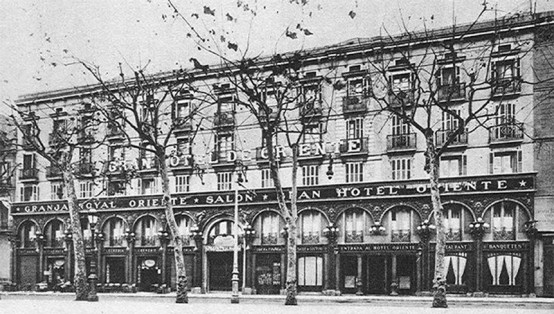

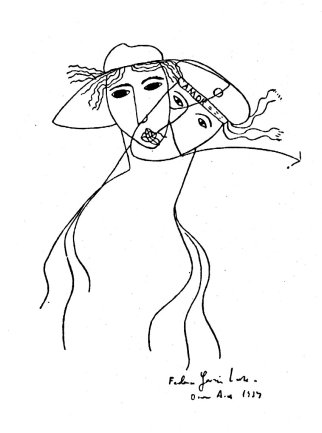

Three great artists frequented the Café La Granja Oriente in Barcelona during the turbulent times of the Spanish Republic in the 1930’s. Who were they? A singer and dancer, a talented poet and a well known lyricist of the 1927 Generation: Miguel de Molina, Federico García Lorca (1898 – 1936) and Rafael de León (1908 – 1982).

According to de Molina, the lyrics of Ojos verdes were drafted the same evening after the premiere of the play by Federico García Lorca: Doña Rosita La Soltera, ‘Lady Rose the Spinster’, performed by the company Margarita Xirgu, at the Teatro Principal, in Barcelona, on 13 December 1935.

Rafael de León arrived at the Café La Granja Oriente and he started to tell a story of sailors and of green eyes to Federico García Lorca and Miguel de Molina. It appears that Rafael de León started to draft the lyrics, until Lorca stated: ‘But Rafael you are plagiarizing me’’. Lorca was referring to his own poem Romance Sonámbulo [3].

Rafael de León replied to Lorca ‘son, you have not invented the colour green’. Despite the friendly disagreement between Rafael de León and Federico García Lorca, they started to play with words and Rafael de León began the drafting of what would become one of the greatest coplas of all times.

Miguel de Molina interrupted Rafael de León joyfully, demanding that as he was the first person to witness the creation of Ojos verdes, he would like to be the first to perform this song’ [4].

The interview given by de Molina sheds some light on who inspired Rafael de León to write the lyrics of Ojos Verdes. It is said that there are at least three versions of Ojos Verdes. This first version, the original, was in the masculine form and sung by a man to a man. I believe, for obvious reasons, this version was never recorded nor performed live.

In the end, Miguel de Molina was not the first to sing this song, at least on stage or in a film. There are many accounts as to who was the first to perform Ojos verdes. However, the most popular versions were recorded by Concha Piquet and later by Miguel Molina himself. Only available in Spanish and without subtitles, to see Concha Piquet version please click here and for the Miguel Molina version please click here.

Manuel Quiroga, one of the music composers of Ojos verdes, proudly stated at the end of his life that it was the best song he had composed. It is said that it was him who offered the song to Concha Piquer, who after reading it asked him, ‘Don’t you think that there is a lot of green in here?’. Quiroga replied : ‘No, Conchita , it is not too much green, it is a beautiful repetition’ [5].

To understand why the lyrics of Ojos verdes were self-censored by its creators we have to put this song into the context of the Spain of the 1930/40’s and the emergence of General Franco. After 1940 the Franco censorship would forbid use of the term “la mancebía”[6] in Ojos verdes, replacing this word by “de mi puerta un día”.

Did my dad and the people of his generation know about the genesis of this song? I doubt they ever realised that the song they sung was related to “the love that dare not speak its name”. Regardless of who was the subject that inspired this lyric, this is a song that teaches us about the universality of love, lust, passion and poetry.

August 2015

— —

Footnotes:

[1] Free translation of the chorus to Ojos verdes.

[2] This was the only interview given to Spanish television, fifty years after Miguel de Molina was exiled from Spain. The complete interview given by Miguel de Molina to the Spanish channel, Canal Sur, in 1990, can be found in YouTube. Only available in Spanish to see the interview please click here.

[3] Federico García Lorca, Romance sonámbulo, from Romancero gitano, 1928. Below there is a fragment of the poem and a free translation.

Verde que te quiero verde.

Verde viento. Verdes ramas.

El barco sobre la mar

y el caballo en la montaña.

— —

Green, I want you green.

Green wind. Green branches.

The ship on the sea

and the horse on the mountain.

[4] Free translation from the interview given by Miguel de Molina in 1990, to Spanish channel, Canal Sur, ibid.

[5] Free translation from: Concha Piquer le preguntó: “Maestro, ¿no le parece a usted mucho verde, mucho verde?”. A lo que le contestó Quiroga: “No, Conchita; ¡qué va a ser mucho verde! Es una redundancia muy bonita”.

[6] The term mancebía has many meanings and some of them have sexual connotations such as dishonest fun, to live in sin without marrying and brothel, to name just three.

You must be logged in to post a comment.