Winter is coming! Treat yourself to a special gift for the new year.

My belief is that to speak a foreign language is a gift.

It allows us to explore new worlds and opens up new work opportunities. I also believe that it is never too late to start learning a language or to pick up from where you left off. Why not take this opportunity to treat yourself to a free consultation and sample lesson with no obligations.

I offer a free 45 minute consultation session which includes:

- a comprehensive assessment of your individual needs;

- drafting a personalised learning plan; and

- an online class taster.

My online classes are tailored to meet each student’s specific requirements and interests. They are designed to motivate and engage students using the latest materials and interactive techniques.

I focus on and apply the principles of the communicative method, teaching in context, whilst maximizing the use of time to make the learning experience pleasurable and rewarding.

Why is it important to learn in context?

Because by simulating real situations through games, conversation, role play, videos, audios, exercises and written work, the connections begin to embed themselves. The strands begin to link up and you will learn quickly and will remember what you have learned.

Travelling or going on holiday to any Spanish speaking country?

I have a tailored 24 lesson intensive online course for you, including home practice modules. No books required. I will provide electronic copies of the lessons.

Register now

Beginners, register before 10 January 2019 for the online winter and Spring term and you will receive a 10% discount off a minimum for 12 classes.

For those with a busy schedule please ask for details of my flexible scheduling.

Enrol now and pay when your lessons commence.

Money back guarantee.

Please ask about terms and conditions.

For further information, please contact me by email at:

hoxtonspanishtutor@gmail.com

or call at:

+ 44 7446 140 335

December 2018

Little Black Angels

(Angelitos negros)

Not many people know that Andrés Eloy Blanco, one of the most prominent Venezuelan writers of all time, was the author of the poem Angelitos negros, Little Black Angels. The poem became the lyrics of the popular song of the same name, which traversed the borders of Venezuela to re-emerge as an anthem against racism in Latin America. It was in this form that I first heard Angelitos negros, and my favourite version is the one by the Venezuelan singer Soledad Bravo. Please click here to listen to this version.

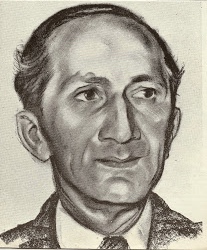

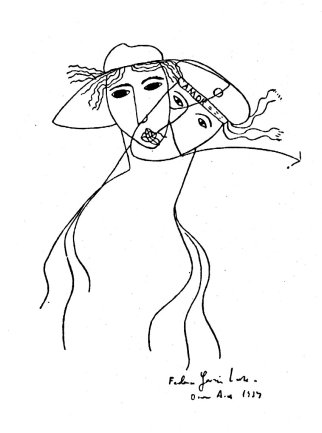

Andrés Eloy Blanco

In my previous article La Copla, I discussed the phenomenon that occurs when a piece of art is somehow appropriated by its people. Similarly, Angelitos negros [1], transcended its creator’s vision to become part of Latin American folklore.

It is said, that Andrés Eloy Blanco [2] may have been inspired by a painting located in the Macarena Basilica, in Seville. The image of the Virgen de Coromoto. Comoroto’s Virgin, Venezuela’s patron, is surrounded by angels, however there are no black angels depicted within this heavenly host.

The poem Angelitos negros starts off by describing the profound sadness of Juana, a woman of African origin, whose little son has died. The second verse is very significant as it describes the mother and her son, “consuming themselves”, suggesting that both are malnourished:

Como ella se consumía,

lo medía con su cuerpo.

Se le iba poniendo flaco

como ella se iba poniendo.

— & —

As she consumed herself,

She measured him against her body.

He was becoming as thin

As she was. [Free translation]

Juana, in the midst of the devastating pain at the loss of her son, hopes that he will be with God. A little angel in the sky, she says. The narrator of the poem counters Juana’s fervent wish; Disabuse my friend, there are no black angels.

It is, lets say, more often than not that white angels surround the Virgin in any painting.

The poet directly addresses the artists of his homeland, these painters of saints and Virgins, reproaching them that they do not paint black angels; and in failing to do so they had denied their own kind. The poem eloquently asks for equality:

No hay pintor que pintara

angelitos de mi pueblo.

Yo quiero angelitos blancos

con angelitos morenos.

There is no painter to paint

angels of my people.

I want white angels

with dark angels. [Free translation]

Andrés Eloy Blanco (1896 – 1955) wrote this poem at a time when issues of racial discrimination were not on the top of the Venezuelan political agenda. His honest views of the world gave voice against the racial discrimination perpetuated in religious art. This was, in many ways, a milestone even in the decades that followed. He remarks in the poem:

no hay una iglesia de pueblo,

donde hayan dejado entrar

al cuadro angelitos negros.

— & —

there isn’t a village church,

where they have allowed

black angels to be painted. [Free translation]

Andres Eloy Blanco is considered to be one of the most talented Latin American poets whilst simultaneously being an adept lawyer and politician. His polemical discourse portrays his concerns about his country and world affairs, which ultimately led him into exile.

Francisco Camacho, Venezuelan university professor, stated that Andres Eloy Blanco lent his poetic talent to those who had no voice and that they could see themselves reflected in his verses [3]. Some political and literary commentators compare this song with the speech of Martin Luther King I have a dream. Andrés Eloy Blanco always condemned intellectual opportunism and had an uncompromising view of the world where ethics should not be negotiable.

Cover of The best of Toña “La Negra”.

The Mexican singer Toña “La Negra” (1912 -1982) was the first to interpret the song Angelitos negros, followed by the Mexican actor and singer Pedro Infante (1917-1957). In order to listen to the version of Toña “La Negra” please click here and for the version of Pedro Infante in the 1946 film Angelitos negros, please click here.

The version sung by Antonio Machín (1903-1977), a Cuban singer, is considered by many to be the best version and it has retained its popularity to this day. However, many other very interesting versions have been recorded over the years keeping this song alive. Please click here for the version of Antonio Machín with the lyrics in Spanish.

Spanish, like the English language, has had a global impact due to its history of proactive colonisation. The power of a word is such that a language mirrors and transmits cultural and moral values of a society, reinforcing them. Angelitos negros is a good example where the model of exclusion is applied in religious art.

Pedro Infante in the 1948 film Angelitos negros.

In 1492, the Spanish Empire began their process of expansion, known as “colonization”. In Latin America the Spanish Empire established a model of exclusion of African and indigenous peoples based upon a racial hierarchy, which still prevails to this day. The use of words such as mulatto (mulato in Spanish), mestizo (mestizo in Spanish) and black (negro) have been part of a large jargon of words which stigmatize, to economically exclude these social ethnic groups.

This “concept of races” and racial stratification perpetuated economical exclusion and has brought devastating consequences to the indigenous and black communities in Latin America to this day.

Angelitos negros gives us another great opportunity to explore different variations of a song to discover which of the many versions is our favourite one. I would like to invite you to surf on YouTube and find your favourite version. Have you found one that you would like to share with us? Please add it below with your comments.

January 2016

Footnotes

[1] For an electronic copy of the poem Angelitos negros in Spanish, please click here.

[2] For further information on the life and works of Andrés Eloy Blanco, please click here to a pdf in Spanish of his biography: Andrés Eloy Blanco y la posteridad, Andrés Eloy Blanco and Posterity, by Oscar Sambrano Urdaneta, Universidad Nacional Abierta.

[3] Free translation from: Prestó su talento el poeta para que los que no tenían voz se vieran reflejados en sus versos. Fragment from Andrés Eloy Blanco: periodismo, modernidad, y política en la Venezuela de la primera mitad del siglo XX, page 22, Profesor Francisco Camacho, Instituto Universitario Experimental de Tecnología Andrés Eloy Blanco. Barquisimeto, Universitary Experimental Institute of Technology Andrés Eloy Blanco, Venezuela.

We do not inherit the earth from our ancestors; we borrow it from our children.

(No heredamos la tierra de nuestros antepasados; la tomamos prestada de nuestros hijos.)

The year ahead is like a blank page waiting to be written. New beginnings are always full of new promise. Just now, I came across the quote above and it has set the tone of my thoughts for the week. I repeated to myself: I do not inherit the earth from my ancestors, I am borrowing it from our children.

It is believed that the previous quotation is part of a longer one that comes from Chief Seattle, a leader of the Native American Suquamish Tribe, who warned the white man: Teach your children what we have taught ours, that the earth is our mother. Whatever befalls the earth befalls the children of the earth. The earth does not belong to man; man belongs to the earth. Humankind did not weave the web of life; we are merely a strand in it. We do not inherit the earth from our ancestors; we borrow it from our children.

This poignant thought focuses on responsibility (responsabilidad in Spanish) rather than on ownership. I believe, we are all responsible for what is given to us by nature, it does not belong to us, nor even to our descendants, as they too will have the same responsibility to deliver in the future.

The term “responsibility” has its origin in the word responsible (responsable in Spanish). It comes from the latin “respōnsum”, “responderē”, which means to answer to. As the English term “to respond” comes from the same root meaning to promise in return and to pledge on.

Following the discovery of a hole in the ozone layer in 1980s, an international agreement took place to resolve the issue. As a result, the international community reduced its dependency on the destructive gases that depleted the ozone layer and now the hole appears to be shrinking. Although this was not a holistic “answer” to the problems we create with our environment, it shows a change of consciousness towards a new way of caring for nature; understanding that we are a part of nature and not a separate entity.

This proactive action reminded me of the plea made by Bruce Witzel in Practical Change, as to what is urgently needed being a change of consciousness about how we relate to ourselves and to our habitat; which I discussed in my previous article Echo, Economy and Ecology.

Another milestone, the recent conference in Paris, the COP21 [1], reached the most ambitious international agreement ever proposed on climate change. Amongst other goals and measures it was agreed to pursue to keep the global temperature increase “well below” 2C (3.6F) above the level they were in the 1850-1899 period.

I, and I hope you too, will acknowledge that we are borrowing the earth from our children. The year ahead is full of new promise and I urge you to engage proactively with the changes needed to harmonize our relationship with the natural world and the nested ecosystems within it wherever and whenever the opportunity arises.

1 January 2016

— —

Footnote

[1] The 21st Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change took place from 30 November to 11 December 2015, in Paris, France.

Treat Yourself to a Gift for the New Year.

My belief is that to speak a foreign language is a gift.

It allows us to explore new worlds and opens up new work opportunities. I also believe that it is never too late to start learning a language or to pick up from where you left off. Why not take this opportunity to treat yourself to a free consultation and sample lesson with no obligations.

I offer a free 45 minute consultation session which includes:

- a comprehensive assessment of your individual needs;

- drafting a personalised learning plan; and

- an online class taster.

My online classes are tailored to meet each student’s specific requirements and interests. They are designed to motivate and engage students using the latest materials and interactive techniques.

I focus on and apply the principles of the communicative method, teaching in context, whilst maximizing the use of time to make the learning experience pleasurable and rewarding.

Why is it important to learn in context?

Because by simulating real situations through games, conversation, role play, videos, audios, exercises and written work, the connections begin to embed themselves. The strands begin to link up and you will learn quickly and will remember what you have learned.

Travelling or going on holiday to any Spanish speaking country?

I have a tailored 24 lesson intensive online course for you, including home practice modules. No books required. I will provide electronic copies of the lessons.

Register now

Register before 10 January 2016 for the online winter term and you will receive a 10% discount off a minimum of 4 classes; and 20% discount for 12 classes.

For those with a busy schedule please ask for details of my flexible scheduling.

Enrol now and pay when your lessons commence.

Money back guarantee.

Please ask about terms and conditions.

For further information, please contact me by email at:

hoxtonspanishtutor@gmail.com

or call:

+ 44 7446 140 335

As promised: Tiramisu recipe.

(Lo prometido es deuda: la receta de Tiramisú.) Tiramisu is another Italian culinary contribution to Argentinean cuisine. It should not come as a surprise that with the successive waves of Italian immigration during the XX century, Tiramisu has become such an appealing dessert in this country. In my previous blog: The Son of the Bride […]

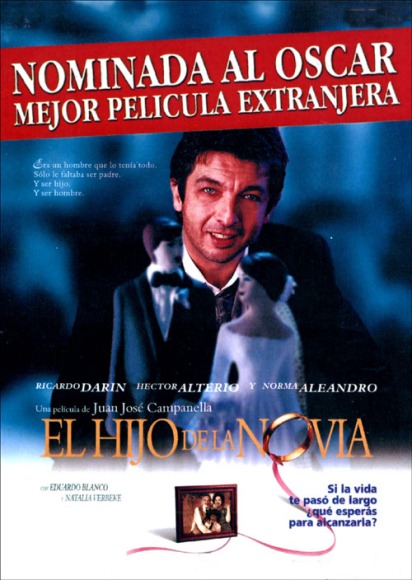

The Son of the Bride and Tiramisu

(El hijo de la novia y Tiramisú)

I have a terribly sweet tooth and one of my favourite deserts is Tiramisu, of which I have a few humorous anecdotes to tell, but not here, unless of course you ask. Surprisingly, the 2001 Argentinean comedy-drama film, El hijo de la novia, The Son of the Bride, springs to mind, a cinematic masterpiece directed by Juan José Campanella [1]. But, why a desert of Italian origin should be discussed in a blog about Spanish language and culture, should come as no surprise, to those of you who follow my blogs. We will look at this later.

The Son of the Bride is a homage to the fragility of human dreams and pursuits. An ode to the ephemeral nature of life, which at times needs to be sweetened, as in the film, with a taste of Tiramisu.

The Hijo de la novia, brings together an exceptional cast of Argentinean actors and actresses and it is mainly two stories that run parallel paths. In the film, the Belvedere family reveal the loves of two different generations: Rafael played by Ricardo Darín and Naty, Rafael’s girlfriend (Natalia Verbeke); Nino, his father (Héctor Alterio) and his mother Norma (Norma Aleandro). The narrative of the film develops the idea of love confronting the vulnerability of life, its fragility and its endurance.

Nino is genuinely in love with Norma after 40 years together. He is burdened by the guilt that he did not fulfill, in his youth, Norma’s wish of marrying in a church and he wants to make amends. However, Norma suffers with Alzheimer’s, and is not aware of Nino’s scheme to put things right. Norma still appears to know those who she always loved. The remarkable performance of the actress, Norma Aleandro, gave me goosebumps and left me with a lump in my throat.

Norma Aleandro, Argentinean icon, film and television actress, who starred in many award winning films.

In the context of Argentina’s perennial economic woes, Rafael runs a restaurant and faces the struggle of a man’s midlife crisis, including his relationship with his girlfriend Naty. She feels excluded because he puts his own self limitations and selfishness before love. Will he find what is true and meaningful in his life?

Natalia Verbeke, Argentinean-Spanish film, theatre and television actress in her great performance as Naty, in The Son of the Bride.

This is a film that crosses the boundaries of love stories and explores the contradictions of the Catholic Church. When the priest refuses to marry his parents on the grounds of ill health, Rafael takes the opportunity to show the priest how detached the Church is from the real world. It is over these sequences of events that Rafael begins to discover what is essential in his life.

El hijo de la novia develops gently in so many layers, as with the layers of Tiramisu; and although during the film the whole recipe is not revealed, we are given a clue as to its key component: mascarpone cheese.

Hoy compramos mascarpone. El especial del día, Tiramisú Norma.

“Today we buy mascarpone. The daily special, Tiramisu Norma”; Rafael instructs Pacheco, the cook in his restaurant, making the point that a Tiramisu cannot be made with any cream cheese, even during the financial crisis that the whole country is going through.

In El hijo de la novia there are images and silent scenes that say more than a thousand words. There are also eloquent dialogues that stayed with me long after the film finished. I hope these dialogues will impact upon Spanish students and trigger a further debate (in Spanish of course).

Italian in origin, Tiramisu has become part of Latin American and particularly Argentinean Cuisine. In the absence of a Tiramisu recipe in the film, I would like to share the delicious Tiramisu recipe from my family, a super-dooper delicious one, from my beloved auntie and godmother Celia. The recipe will be available in my next blog.

¡Hasta la próxima!

Footnotes

Footnotes

[1] A copy of the complete film El hijo de la novia in Spanish without subtitles can be found in YouTube, please click here.

A copy of a DVD of The son of the bride, with English subtitles, can be obtained from Amazon.es

… …

This article is part of the series: Recipes from the big screen. See Spanish and Latin American Cuisine (Part1) – Recetas de películas; and Recipes from the big screen. See Spanish and Latin American Cuisine (Part2) A Recipe for Almond Cake. Why is This Recipe so Special?

Marimorena – Is it sexist to use this word in Spanish?

The origin of the expression ‘marimorena‘ is not well known. What is certain is that it arose in the mists of the late 1500s during the emergence of imperial Spain. A story places Mari Morena, a woman, at the centre of this meaningful expression, associated with scandal, trouble, fights and quarrels. I will refer to the colorful version of the story given in the 1899 publication España Moderna, Modern Spain. It intrigues me as to why the name of a woman should become so associated with those actions that are generally more attributed to men.

The Royal Spanish Academy Dictionary clearly states that marimorena is a colloquial feminine noun, meaning: to fight, quarrel and brawl [1].

The version of the story appearing in the 1899 publication España Moderna, Modern Spain [2] unveils significant details as to how the name of Mari Morena has transcended the centuries.

By 1579 there was a well established taberna, tavern, in Cava Baja, a street in Madrid run by Alonso de Zayas and Mari Morena, his wife.

Street sign of Cava Baja located in the centre of Madrid. Tiles by ceramist Ruiz de Luna. Courtesy of photographer Pedro Reina © Pedro Reina

The Cava Baja is one of the oldest streets of Madrid and by the 1600s would have been the hub for arrivals and departures, for carriers of merchandise and couriers bringing the mail to the provinces. Later, it became synonymous as the place where groups of thugs used to frequent.

In 1579, Alonso de Zayas and Mari Morena became very well known in Madrid following a high profile judicial court case which took place as a result of a quarrel that arose in their tavern. Alonso de Zayas and Mari Morena had refused to serve their finest wine, contained in cueros de vino, leather wine holders, to thirsty soldiers, because it was reserved solely for members of the Court and their more illustrious customers.

According to the chronicles of the time Mari Morena stood her ground during quarrels in her tavern better than anybody else. She was known as a barmaid ready to ‘crack heads’ to resolve any quarrels by those who did not want to pay or were drunk; and her name and manner survive to these days.

Then as an extension of her name the expression se armó la marimorena meaning “it was a serious quarrel or fight”, entered the language.

Although this story tells us about a remarkable woman who knew how to fight her corner; it appears that the meaning of this expression has evolved. I agree with those who argue that this expression may perpetuate the stereotypical view of women as being quarrelsome. Perhaps, the challenge which faces us today is to restore the original meaning of marimorena as an expression to describe a woman who stands up for herself.

September 2015

— —

Footnotes

[1] For the Real Academia Española, Spanish Royal Academy’s definition of marimorena, please click here.

[2] España Moderna, Modern Spain, año II, número 128, page 115, agosto de 1899, Madrid. To access the pdf file of this publication, please click here.

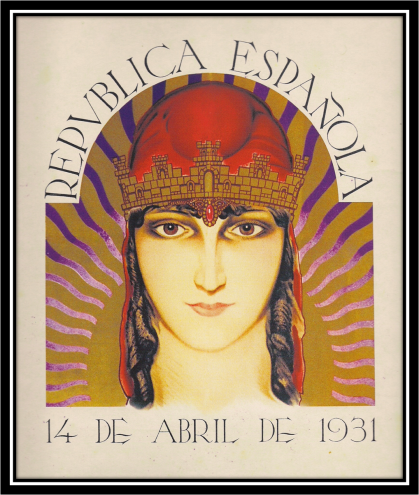

La Copla

On the cusp of 20th century, amidst the cafés cantantes and cafés de marineros, bars with live music and those frequented by sailors, the more cosmopolitan ‘ambientes‘ [1] of Spain gathered to indulge in the bohemian lifestyle. One can only imagine the subversive appeal of such illicit places, with drinking and both flamenco and pasodoble performances, attracting thrill-seeking members of a conservative society to a risqué underworld. This vibrant scene gave birth to the Copla.

As with all partisan movements a counter-narrative develops. The lyrics of Ojos Verdes and Las cosas del querer (as discussed in my previous two articles), and of the majority of coplas, are made up of language, both direct and colloquial. They are filled with innuendo and double meaning to avoid censorship of forbidden or marginal themes: social division, gypsies, imprisonment, prostitution, good and bad luck, forbidden or hidden love and homosexuality.

The people sang because music would have kept spirits high during the tragic 1930’s. The pain and suffering was well portrayed in some of these lyrics, such as: “Gypsy woman wandering across the world, singing and dancing, singing I seek relief of my grief” [2].

Suspiro de España, Sigh of Spain, may have been the first copla ever written [3]. This was performed in the film of the same name by Spanish singer and actress Estrellita Castro (1908-1983). The lyrics reflected the nostalgia of those forced to go into exile during the Spanish Civil War and of their love for their homeland. To listen to the version by Estrellita Castro please click here .The song starts at 2.05 minutes.

The copla La Diputada, The Congresswoman, first sung by Amalia Molina in 1932, is a clear example of strong feminist lyrics. To listen to the song: please click here [4]. Please see below a fragment of the lyrics in Spanish and English:

Llegó la hora del feminismo,

y como siempre fui avispada,

y en todas partes me llevo algo,

me llevé el acta de diputada.

En el congreso con Luis de Tapía,

estoy actuando de adalid,

¡Viva el divorcio! ¡Vivan mis manos!

Qué aún no han cosido, ¡ni un calcetín!

— —

It has arrived the time for feminism,

and as always I was shrewd,

and as everywhere I achieve something

I took the role of deputy.

At the congress with Luis Tapia,

I am acting as champion,

Long live the divorce! Long live my hands!

They have not yet sewn, not even a sock! [5]

The radio was central to popular post-war entertainment, also post-war the Copla was the only genre that pushed the boundaries of what was permissible to sing, touching on the thorniest issues as no other genre did at that time.

It is noteworthy that whilst coplas appeared to have sprung from the bohemians and Republicans of Spanish society, the Franco propaganda regime would appropriate those symbols, which Spanish people could identify as Republican, and turned them into the “official” Spanish popular culture.

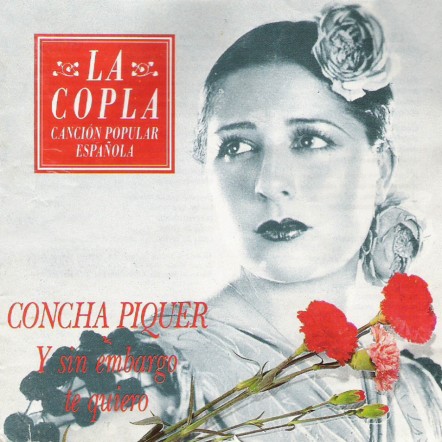

Concha Piquer (1906-1990) one of the most renowned and talented interpreters of coplas is associated with the Franco regime. Some people nowadays unfairly only see the coplas as the official music of the Franco regime in Spain and therefore as something to reject.

Three of the most representative authors of coplas are Rafael de León, Manuel López Quiroga and Antonio Quintero, together known as the Trio Quintero. Rafael de León, considered to be a poet of the 1927 generation, wrote approximately 5000 coplas with Antonio Quintero and Manuel López Quiroga and 8000 in total.

Many others are worthy of mention, amongst them Antonio Machado, Federico García Lorca, Violeta Parra and Jaime Dávalos, to name a few of the Spanish and Latin American artists who have written unforgettable coplas.

Coplas are the voice of the Spanish people at a significant time in their history, regardless of whether or not coplas were Republican born or fostered by the Franco regime I am of the opinion that they belong to the people and , as Manuel Machado (1874-1947) says:

Until people sing the coplas, there are no coplas, and when the people sing them, then nobody knows the author. Such is the glory, Guillen, of those who write songs, to hear people say that no one has written them. You hope that your coplas end with the people, despite that they will no longer be yours and will belong to everybody else. That is when you melt your heart in the popular soul. What is lost of recognition is gained in eternity [6].

September 2015

This is a follow up to two previous articles: The Things of Love and Green Eyes, published in August 2015.

— —

Footnotes

[1] Ambiente: ambience, set of characteristics of a social group.

[2] Free translation from: Gitana, gitana, gitanilla errante cruzó el mundo entero, cantando y bailando buscó en las canciones alivio a mi duelo.

[3] Suspiro de España was written by by Antonio Álvarez Alonso and composed by Juan Álvarez

Alonso.

[4] La Diputada was written by De Carrere and Font de Anta.

[5] Fragment from the copla La Diputada, free translation.

[6] Free translation from the poem:

La copla

Hasta que el pueblo las canta,

las coplas, coplas no son,

y cuando las canta el pueblo,

ya nadie sabe el autor.

Tal es la gloria, Guillén,

de los que escriben cantares:

oír decir a la gente

que no los ha escrito nadie.

Procura tú que tus coplas

vayan al pueblo a parar,

aunque dejen de ser tuyas

para ser de los demás.

Que, al fundir el corazón

en el alma popular,

lo que se pierde de nombre

se gana de eternidad.

To listen to La copla of Manuel Machado recited by Vicent Camps, please click here. Only available in Spanish without subtitles.

The Things of Love

(Las cosas del querer)

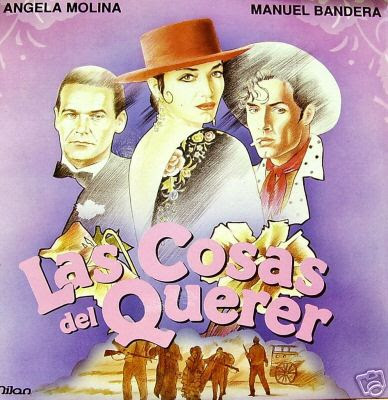

Following my previous article, Ojos Verdes, Green Eyes, I received requests to share some thoughts on the beautiful copla, Las cosas del querer, The Things of Love, as well as the 1989 film of the same name. In honour of this here are my musings. For a moment of pure pleasure, listen to Las cosas del querer sung, in Spanish, by Angela Molina and Manuel Banderas: please click here. Do return as there is more to come.

See below the chorus translation:

Son las cosas de la vida,

son las cosas del querer,

no tienen fin ni principio,

ni tien(en) [1] cómo ni por qué.

Tú eres alto y yo bajita,

tú eres rubio y yo tostá;

tú de Sevilla la llana

y yo de Puerto Real.

Que no tiene na’ [2] que ver

ni el color ni la estatura

con las cosas del querer.

Lo nuestro tiene que ser

aunque entre el uno y el otro

levanten una pared.

— —

These are the things of life,

these are the things of love,

they don’t have an end nor beginning,

they don’t have a how nor a why.

You’re tall and I am short,

you’re blond and I am brown;

you’ re from the Sevilla plains

and I’m from Puerto Real.

These have nothing to do,

colour or height,

with the things of love.

Our love is meant to be

even if between us

they build a wall.[3]

The passion conveyed, by these great Spanish voices, through the coplas have always delighted audiences with their heartfelt lyrics and these still resonate to this day and stir my emotions.

Las cosas del querer, The Things of Love, is a copla, which became renowned during the unsettled times of 30’s and 40’s Spain. Composed by Rafael de León and Antonio Quintero, possibly the greatest copla composers of all time, and sung by, amongst others, Miguel de Molina. The lyrics convey the universal message of the unconditional nature of love.

The legendary life of singer Miguel Molina is unveiled in his autobiography Botín de guerra, Spoils of War, and its similarities with the plot of the 1989 film Las cosas del querer led many to believe that the film was inspired by his life [4].

Written and directed by Jaime Chávarri the film is a celebrated piece of Spanish musical cinema. It became so successful in Spain and Latin America that a sequel was filmed in 1995.

Anticipating an abrupt departure brought about by the forced exile of the main character Mario, the film begins by framing the plume of a steam-train and its boarding whistle call. Mario, portrayed by Manuel Banderas, is standing in the carriage with a bruise on his face. Mario’s voiceover sets the tone that follows:

“We never will see each other again, the three of us know that. I can no longer live in this damned country and I am not only leaving because I’m cast away but also because I do not know what to do with my life and with you.

We’ve been so together these years, the three of us. Juan: you and me, we met before. We lost the war in the same regiment and that afternoon the bombing near the hospital changed our lives.” [5]

Then, as if Mario were looking at the past through a mirror, the story begins to be told. The Spanish Civil War is coming to an end and as a game of fate Mario, Pepita and Juan are reunited again.

Manuel Banderas, as Mario, Ángel de Andrés López, as Juan and Ángela Molina, as Pepita in the film Las cosas del querer.

The story is wonderfully narrated and intertwined with songs such as: La bien pagá, She, The Well Paid; Compuesta y sin novio, Composed and Without Boyfriend; Te lo juro yo, I Swear; and many of the best known songs of this time.

Mario’s story has a strong resemblance to the life of Miguel de Molina. Together with Manuel Banderas, two other great Spanish stars: Ángela Molina (Pepita) and Ángel de Andrés López (Juan) tell the story of three artists that join together as a musical group. Mario, gay and a Republican, is in love with Juan whereas Juan is in love with Pepita; and whilst Pepita is in love with Juan, she faces the same equality issues that the women of today face in striving for an independent career.

The three confront the post Spanish Civil War times encountering throughout the prejudice of a conservative society that will lead to Mario’s exile.

The three confront the post Spanish Civil War times encountering throughout the prejudice of a conservative society that will lead to Mario’s exile.

Often we forget important moments from our past: I am talking about the histories of those who inhabited our homes a few generations ago and perhaps what Las cosas del querer does best, is to bring to mind the memories of a not very remote past that we should not forget … and of Miguel de Molina of whom someone has said: He could be blamed for being the most arrogant and handsome, and in the contours of Sierra Morena, there was no one more beautiful, kinder or honest [6].

The complete film is available on YouTube, to see the film Las cosas del querer, only in Spanish without subtitles, please click here.

August 2015

— —

Footnotes:

[1] tien: tienen

[2] na’: nada

[3] Free translation.

[4] At the beginning of the film credits, thanks are given to Quintero, León, Quiroga, Mostazo y Solano and many other authors that made the Andalusian song /Canción Andaluza. At the end of the film we are warned that any similarities with reality would have been pure coincidence.

There has been some controversy as to whose life may have inspired the film Las cosas del querer. Some have stated that the character Mario was bluntly inspired by the endearing life of the legendary Molina. Miguel de Molina himself expressed in his autobiography Botín de guerra, Spoils of War, his devastation because he did not receive a penny of copyright revenue that he understood belonged to him.

[5] Free translation from: Ya nunca volveremo(s) a verno(s), lo sabemo(s) los tre(s). Yo ya no puedo vivir en este jodido paí(s) y no me voy solo porque me echan, me voy también porque no sé que hace(r) con mi vida y con vosotro(s).

Hemos estado tan junto(s) esto(s) año(s) los tres. Tú y yo Juan nos conocimo(s) antes. Perdimo(s) la guerra en el mismo regimiento y aquella tarde el bombardeo cerca del hospital cambió nuestras vidas.

[6] Free translation from: Antonio Vargas Heredia, podría achacarse aquello de que era él más arrogante y el mejor plantao, y por los contornos de Sierra Morena, no lo hubo más guapo, más bueno ni honrao.

Green Eyes

(Ojos verdes)

We knew when dad was happy in the mornings. He used to sing the songs he learned from grandma Chiquita (Petit), as we used to call her. Dad used to sing Ojos verdes, Green Eyes, one of the greatest coplas of all times. He said that Concha Piquer made this song known in the film Filigrana, Filigree, in 1949. As with any other great song, the genesis of Ojos verdes has its own legend and my dad’s account may not be have been the whole story.

I still remember the chorus that my father used to sing:

Ojos verdes, verdes como la albahaca.

Verdes como el trigo verde

y el verde, verde limón.

Ojos verdes, verdes, con brillo de faca,

que están clava(d)ítos en mi corazón.

Pa(ra) mí ya no hay soles, luceros ni luna,

no hay más que unos ojos que mi ví(d)a son.

Ojos verdes, verdes como la albahaca.

Verdes como el trigo verde

y el verde, verde limón.

— —

Green eyes, green as basil.

Green like the green wheat

and the green, green lime.

Green eyes, green, with the brightness of a dagger,

They are nailed in my heart.

For me there are no suns, constellations or moons,

There is nothing else than those green eyes that are my life

Green eyes, green as basil.

Green like the green wheat

and the green, green lime. [1]

In 1989, I heard a new version of Ojos verdes by Manuel Banderas, in the film Las cosas del querer, The Things of Love. The screening awoke my curiosity as to who could have inspired such a masterpiece of Spanish music. To see a clip of Manuel Bandera’s version please click here.

In 1990, fifty years after his exile from Spain, Miguel de Molina (1908 – 1993), one of the most renowned Spanish copla singers revealed, during an interview to the Spanish channel Canal Sur, significant details of the very first moments when the lyrics of Ojos Verdes were written [2].

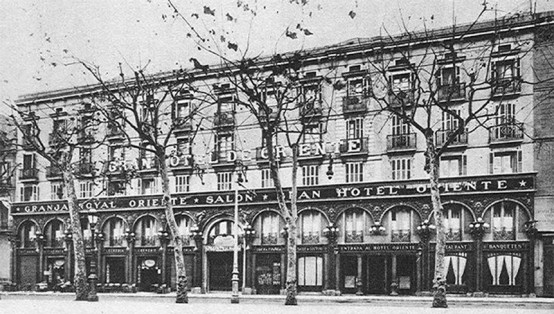

Three great artists frequented the Café La Granja Oriente in Barcelona during the turbulent times of the Spanish Republic in the 1930’s. Who were they? A singer and dancer, a talented poet and a well known lyricist of the 1927 Generation: Miguel de Molina, Federico García Lorca (1898 – 1936) and Rafael de León (1908 – 1982).

According to de Molina, the lyrics of Ojos verdes were drafted the same evening after the premiere of the play by Federico García Lorca: Doña Rosita La Soltera, ‘Lady Rose the Spinster’, performed by the company Margarita Xirgu, at the Teatro Principal, in Barcelona, on 13 December 1935.

Rafael de León arrived at the Café La Granja Oriente and he started to tell a story of sailors and of green eyes to Federico García Lorca and Miguel de Molina. It appears that Rafael de León started to draft the lyrics, until Lorca stated: ‘But Rafael you are plagiarizing me’’. Lorca was referring to his own poem Romance Sonámbulo [3].

Rafael de León replied to Lorca ‘son, you have not invented the colour green’. Despite the friendly disagreement between Rafael de León and Federico García Lorca, they started to play with words and Rafael de León began the drafting of what would become one of the greatest coplas of all times.

Miguel de Molina interrupted Rafael de León joyfully, demanding that as he was the first person to witness the creation of Ojos verdes, he would like to be the first to perform this song’ [4].

The interview given by de Molina sheds some light on who inspired Rafael de León to write the lyrics of Ojos Verdes. It is said that there are at least three versions of Ojos Verdes. This first version, the original, was in the masculine form and sung by a man to a man. I believe, for obvious reasons, this version was never recorded nor performed live.

In the end, Miguel de Molina was not the first to sing this song, at least on stage or in a film. There are many accounts as to who was the first to perform Ojos verdes. However, the most popular versions were recorded by Concha Piquet and later by Miguel Molina himself. Only available in Spanish and without subtitles, to see Concha Piquet version please click here and for the Miguel Molina version please click here.

Manuel Quiroga, one of the music composers of Ojos verdes, proudly stated at the end of his life that it was the best song he had composed. It is said that it was him who offered the song to Concha Piquer, who after reading it asked him, ‘Don’t you think that there is a lot of green in here?’. Quiroga replied : ‘No, Conchita , it is not too much green, it is a beautiful repetition’ [5].

To understand why the lyrics of Ojos verdes were self-censored by its creators we have to put this song into the context of the Spain of the 1930/40’s and the emergence of General Franco. After 1940 the Franco censorship would forbid use of the term “la mancebía”[6] in Ojos verdes, replacing this word by “de mi puerta un día”.

Did my dad and the people of his generation know about the genesis of this song? I doubt they ever realised that the song they sung was related to “the love that dare not speak its name”. Regardless of who was the subject that inspired this lyric, this is a song that teaches us about the universality of love, lust, passion and poetry.

August 2015

— —

Footnotes:

[1] Free translation of the chorus to Ojos verdes.

[2] This was the only interview given to Spanish television, fifty years after Miguel de Molina was exiled from Spain. The complete interview given by Miguel de Molina to the Spanish channel, Canal Sur, in 1990, can be found in YouTube. Only available in Spanish to see the interview please click here.

[3] Federico García Lorca, Romance sonámbulo, from Romancero gitano, 1928. Below there is a fragment of the poem and a free translation.

Verde que te quiero verde.

Verde viento. Verdes ramas.

El barco sobre la mar

y el caballo en la montaña.

— —

Green, I want you green.

Green wind. Green branches.

The ship on the sea

and the horse on the mountain.

[4] Free translation from the interview given by Miguel de Molina in 1990, to Spanish channel, Canal Sur, ibid.

[5] Free translation from: Concha Piquer le preguntó: “Maestro, ¿no le parece a usted mucho verde, mucho verde?”. A lo que le contestó Quiroga: “No, Conchita; ¡qué va a ser mucho verde! Es una redundancia muy bonita”.

[6] The term mancebía has many meanings and some of them have sexual connotations such as dishonest fun, to live in sin without marrying and brothel, to name just three.

You must be logged in to post a comment.